The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate how with the help of a mathematical model the set of concepts which are constitutive for Habermas’ conception of UP can be systematically generated, and how its coherence and consistency can be reconstructed.

(Note: in the published text of 1985 I have replaced everywhere the term ‘competence’ by the term ‘capacity’ as the more appropriate term. I made there also a couple of alterations aimed at improving and clarifying that published text .)

I

Habermas has introduced the concept ‘Universal Pragmatics’ (UP) in his (1976a and b) and in his (1980), (1981a and b). In these writings it is the name he uses for a general theory of social interaction , which is the reconstructive-philosophical part of his theory of society. Its aim is to reconstruct in an analytical manner, that is, regardless of historical time and space, the overall structure of a social interaction situation. According to Habermas’ reconstruction all social actions and events have, in all contexts and on all levels of analysis, a common multidimensional, intersubjective structure. In this paper I can not give a detailed analysis of his reconstruction. I have to refer to my dissertation (1982). A short outline of my reconstruction is given in my (v.Doorne , Ruys 1984) and (v.Doorne 1986).

To give at least an impression of Habermas’ differentiated (speechact theoretic) pragmatic approach I quote a passage from his (1981, 159) that, in my opinion, is quite significant:

‘In saying something within an everyday life context, speaker not only refers to

– something in the objective world ( as the totality of what is the case), but simultaneously to

– something in the social world (as the totality of legitimate interpersonal relationships), and to

– something in speaker’s own subjective world (as the totality of manifestable subjective experiences to which he/she has priviledged access).

This is how the tripartite network between utterance and world presents itself intentione recta, that is from speaker’s (and hearer’s) perspective.

The same network can be analysed intentione obliqua, from the perspective of the lifeworld, or the background of shared assumptions and procedures, in which any particular piece of communication is inconspicuously embedded from the very beginning. From this viewpoint language serves

– the function of cultural reproduction (or keeping traditions alive): (…)

– the function of social integration (or co-ordinating the plans of different actions in social interaction): (…)

– the function of socialization (or of the cultural interpretation of needs): (…).’

II

As a result of my reconstruction of Habermas’ UP I consider (partly amending his terminology and adding to it) the following set of concepts as indispensable: objectivity, subjectivity, normativity, intersubjectivity and sociality. I feel encouraged to defend this position by Habermas’ recent analysis (1996), in which he reconstructs the linguistic-pragmatic, conceptual infrastructure of social interaction.

These five concepts determine in their mutual interdependence the general characteristics of social relations. It is only with the help of a mathematical model and in a longstanding dialogue with Pieter Ruys, professor of mathematical economics, that I have been able to articulate in a precise way the complex interrelatedness of the five constitutive concepts as they are introduced in Habermas’ writings. The mathemathical model I use has been developed by Ruys, and he calls it the tripolar interaction model. Making use of this model in my interpretation of Habermas’ conception I have developed a Habermasian tripolar model of social interaction. I claim that my interpretation is consistent with the characteristics of the (mathematical) tripolar interaction model as well as with the (philosophical, pragmatic) structure of Habermas’ conception of social interaction. Interpretation of the formal model in terms of what I call a basic model of social interaction results in a consistent, coherent, and fruitful set of analytical concepts that are appropriate to generate the five structuring concepts of Habermas’ UP. I introduce it under III.

Given the space limits of this paper I can only outline the basic model. Elsewhere I claim that with the conceptual means of the basic model two new sets of interdependent concepts can be generated and articulated, that is, the concepts of an action-model (refering to social interaction between agents) and the concepts of a system-model (refering to social interaction between domains). For this purpose the concepts of the basic model have to be empirically specified to make them apt to refer to social phenomena in different contexts and on different levels of aggregation. There I claim further, that the basic model, that is, the action- and system-model together in their mutual interdependence, constitutes the general frame of social interaction required by Habermas’ theory of society.

III

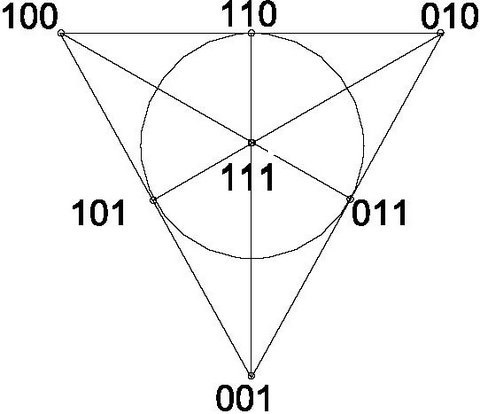

The tripolar interaction model that I take as my point of departure, is a purely formal model, that is, void of empirical content. Its structure is determined by the interdependence of seven positions, represented by points, and seven relations, represented by lines (see figure 1). For the mathematical features of the operator that commands the interaction between points and between lines I refer to (vDoorne/Ruys 1986, section 3.1 and 3.2, 208-212).

Figure 1: the formal tripolar model of interaction

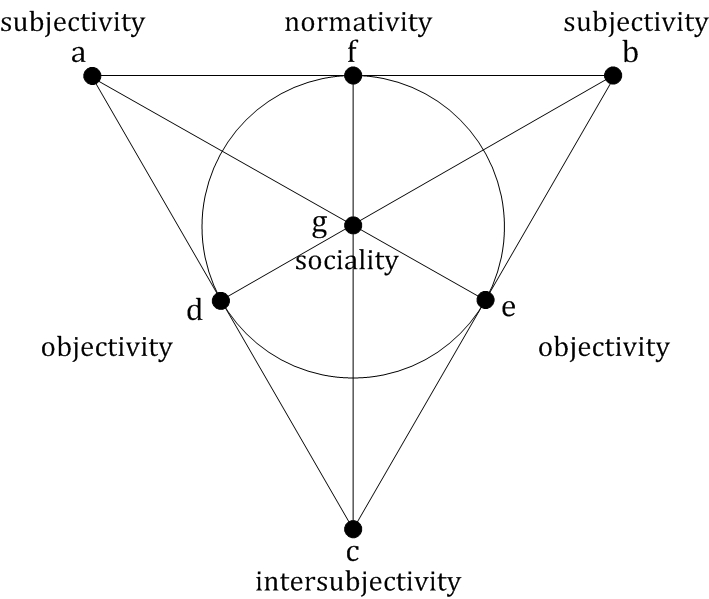

Figure 1 represents the structural nexus of positions and relations. Figure 2a (see below) represents my interpretation of the positions of figure 1 in terms of primitive concepts* referring to the constituent components of social interaction which are necessary and sufficient for generating the five structuring concepts of Habermas. These are defined by the (interpreted) relations of figure 1 represented in figure 2b (see below).

The basic model

In the mathematical model (Figure 1) three groups of positions can be distinguished, each group with different characteristics. The presence of a characteristic is indicated by the cipher 1. There are three positions (100, 010, 001) having only one characteristic. There also are three positions with two characteristics (110, 011, 101). And there is one position with three characteristics (111). I interpret all seven positions as representing capacities. And I call the capacities represented by the three positions having only one characteristic, separate capacities; the three positions with two characteristics intermediate capacities; and the position with three characteristics integrative capacity.

With the philosophical interpretation I give to the three separate capacities, I alter the formal equivalence of the three positions with one characteristic by conceptually defining two of them (100 and 010) as agent capacity. For these two positions this capacity is understood in the same sense, albeit that the capacity is unique in the two cases, understood as being irreducible to the other. This difference will be coded as + and -. From the perspective of a general theory of society I interpret the third position (001) as (capacity of )mediating resources; it equally represents a separate capacity, .

For the interpretation of the intermediate capacities, represented by the three positions with two characteristics (110, 011, 101), another alteration of their formal equivalence has to be made, that is, in line with the differentiation of the conceptual content of the three separate capacities. The positions (011) and (101) represent the capacity of interaction between each of the two different agent capacities (+ and -) and the capacity of mediating resources, that is, as belonging to the relations (100, 101, 001) and (010, 011,001) respectively. I define this capacity as embodiment + and –. Position (110) as belonging t0 the relation (100,110,010), has to be defined differently due to the differentiation of the conceptual definition of the three separate capacities. In my interpretation it represents the capacity of interaction between the agent capacities + and -, and I call this capacity common framing. The thus defined three intermediate positions represent the interaction between separate capacities, combining their characteristics.

There is still another reason to interpret the three positions with two characteristics as intermediate capacities. Each of them represents also the relation between a separate capacity and the integrative capacity (111): (011) as belonging to the relation (100,111,011), (101) as belonging to the relation(010,111,101), and (110) as belonging to the relation (011,110,101). From the angle of their being part of these relations another additional interpretation is required of the three intermediate capacities, different from, and complementary to the interpretation already given.

I interpret position (011) , belonging to the relation (100,111,011), as (capacity of) embodiment – , this time in the sense of objectdetermination +, because it represents the capacity of interaction between agent competence + (100) and what I will call (capacity of) social integration represented by position (111). This interpretation of position (111) has to be qualified in the sense that this position as being part of the relation (100,111,011) represents social interaction under the angle of its objectivity. Similarly, I call (101) as belonging to the relation (010,111,101) (capacity of ) object determination – , because it represents the capacity of interaction between the agent capacity – (010) and the (capacity of) social integration (111), equally to be qualified under the angle of its objectivity. I call position (110) as belonging to the relation (110,111,001) (the capacity of) common framing because as part of this relation the position represents (the capacity of) integration between the separate (capacity of) mediating resources (001) and the (capacity of) social integration (111), in as far as this last capacity is considered under the angle of its commonly framed use of the mediating resources involved.

There is still another, last, reason to interpret the three positions with two characteristics as intermediate capacities. Each of them represents the capacity of interaction with the other two intermediate capacities. I call (110) interpreted as representing the capacity of interaction between (the capacities of ) embodiment + (101) and of embodiment -(011) (capacity of) common framing of embodiment , and interpreted as representing the interaction between (the capacities of) object determination + (011) and of object determination – (101) the (capacity of ) common framing of object determination . I call (101) interpreted as capacity of interaction between (the capacity of ) object determination + (011) and (the capacity of) common framing (110) the equivalent capacity d. In the same sense I call (011) interpreted as capacity of interaction between (the capacity of ) object determination – (101) and (the capacity of) common framing (110) the equivalent capacity of e.

Finally, the remaining position (111) with its three characteristics represents a threefold integrative capacity with regard to the relations of which this position is part: respectively (110,111,001),(100,111,011),(010,111,101). First, (111) represents the capacity of interaction between capacities of common framing (110) and of mediating resources (001). I call (111) in this relation social interaction with regard to common framing the use of mediating resources. Second, (111) represents the capacity of interaction between agent capacity + (100) and object determination + (011). I call (111) as part of this relation social interaction with regard to the common framing of object determination +. Third, (111) represents the capacity of interaction between agent capacity – (010) and (the capacity of ) object determination – (101). I call (111) as part of this relation social interaction with regard to the common framing of object determination – (101). Thus, according to my definition, (111) represents a capacity of interaction such that it integrates the six other capacities. Therefore, I have called this capacity integrative capacity.

In this way, I have interpreted all the positions of the mathematical tripolar model in terms of well defined primitive concepts which , so I argue, are necessary and sufficient to develop the concepts for a general theory of society. The positions in figure 2a represent these primitive concepts (in shorthand), and instead of the algebraic codes assigned to the seven positions I use the first seven letters of the alphabet (lower case) to name them, as follows:(100) a=agent capacity +, (010) b=agent capacity -, (001) c= (capacity of) mediating resources , (101) d=(capacities of) embodiment + and -, (011) e= (capacities of ) embodiment – and +, (110) f =(capacity of) common framing, (111) g=integrative capacity.

Figure 2a: the basic model (primitive concepts)

In Table 1 I summarize the foregoing:

Table 1

a,b,c : separate capacities

– a agent capacity +

– b agent capacity –

– c resource capacity

d,e,f : intermediate capacities,

– d

. capacity of embodiment + (d as intermediate in the relation (a,d,c).

. capacity of embodiment – (d as intermediate in the relation (b,g,d). I will specify this capacity as object determination

. capacity of equivalent embodying capacity+ and object determination – (due to the capacity of common framing f as intermediate in the relation (d,f,e);

– e

. capacity of embodiment – (d as intermediate in the relation (a,d,c).

. capacity of embodiment + (d as intermediate in the relation (b,g,d)),

. capacity of equivalent embodying capacity – and object determination + ( due to the capacity of common framing f as intermediate in the relation (d,f,e)

– f

. capacity of common framing of agent capacities + and – (f as intermediate in the relation (a,f,b))

. capacity of common equivalent framing embodiment + and object determination – (f as intermediate in the relation (d,e,f))

. capacity of common framing in the use of mediating resources (f as intermediate in the relation (f,g,c));

g : integrative capacity

. capacity of integration regarding the capacities of object determination + and of the capacity of embodiment – (g as capacity in the relation (a,g,e)),

. capacity of integration regarding the capacity of object determination – and of the capacity of embodiment + (g as capacity in the relation (b,g,d))

. capacity of integration regarding commonly framed use of mediative resources (g as capacity in the relation (f,g,c)),

With the help of the analytically constructed primitive concepts of Table 2a and given the definition of their interrelatedness I am now able to generate systematically the concepts needed for a UP. The five structuring concepts generated are represented in figure 2b by the seven relations. Each of them is conceptualized in terms of the interactive nexus of three primitive concepts summarized in Table 1, such that each time the three concepts concerned belong to the same relation: the relation of respectively subjectivity +, subjectivity -, objectivity +, objectivity -, normativity, intersubjectivity and sociality (as shown in Table 2).

Figure 2b: the basic model (structuring concepts)

Table 2

(a,d,c) and (b,e,c): two relations of subjectivity (+ and -)

in both cases constituted by a action competence (a and b), mediative resources (c) and embodiment + (d) and embodiment – (e);

(a,g,e) and (b,g,d): two relations of objectivity (+ and -)

in both cases constituted by a action competence (a and b), object determination+ (e) and object determination – (d), and social interaction regarding commonly framed intersubjectively mediative resources (g);

(a,f,b) : a relation of normativity

constituted by the two action competences (a and b) and common framing of action competences (f);

(f,g,c) : a relation of intersubjectivity

constituted by common framing of action competences (f), social interaction regarding the intersubjective objectivity of embodiment + and – (g), and mediative resources (c);

(f,d,e) : a relation of sociality

constituted by the common framing of action competences (f), the equivalence of (d) with objectdetermination + and embodiment-, and the equivalence of (e) with objectdetermination – and embodiment+.

References

Doorne, F. van (1982), Naar nieuwe grondslagen van sociaal-wetenschappelijk onderzoek. De ontwikkeling van Habermas’ reconstructieve filosofie in de jaren 1960-1980. Tilburg: Gianotten.

Doorne, F. van , Ruys, P.(1984), Die Struktur einer Sprechhandlung in Habermas’ Forschungsprogramm. Formale Analyse mit den Mitteln des Tripolaren Modells, in K. Apel, W.van Reyen (eds.), Rationales Handeln und Gesellschaftskritik, Bochum:Germinal, 201-218.

Doorne, F.van (1986), Foundational Research as Intermediate Function between Everyday and (Socio-)Scientifuc Action. A Research Design, in W. Leinfellner, F. Wuketits (eds.), The Tasks of Contemporary Philosophie, Wien:Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky

Habermas, J. (1976a), Was heisst Universalpragmatik ?, in K.Apel (ed.), Sprachpragmatik und Philosophie. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkampf, 174-272.

Habermas, J. (1976b), Some Distinctions in Universal Pragmatics, Working Paper, in Theory and Society 3:155-167.

Habermas, J. (1980), Handlung und System – Bemerkungen zu Parsons’ Medientheorie, in W.Schluchter (ed.), Verhalten, Handeln und System, Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkampf, 68-105

Habermas, J.(1981a), Interpretatieve sociale wetenschap versus radicale hermeneutiek, in Kennis en Methode 5:4-23 (quoted from the Manuscript of the English Version 5-6)

Habermas, J. (1981b), Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns I und II, Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp

Habermas, J. (1996), Die Einbeziehung des Anderen, Frankfurt a.M: Suhrkamp